“We want to believe the best of who we are, and ignore and deny the worst. The most intriguing moment of a story is when a villain begins to convince a reader that what he is doing may actually be necessary…”

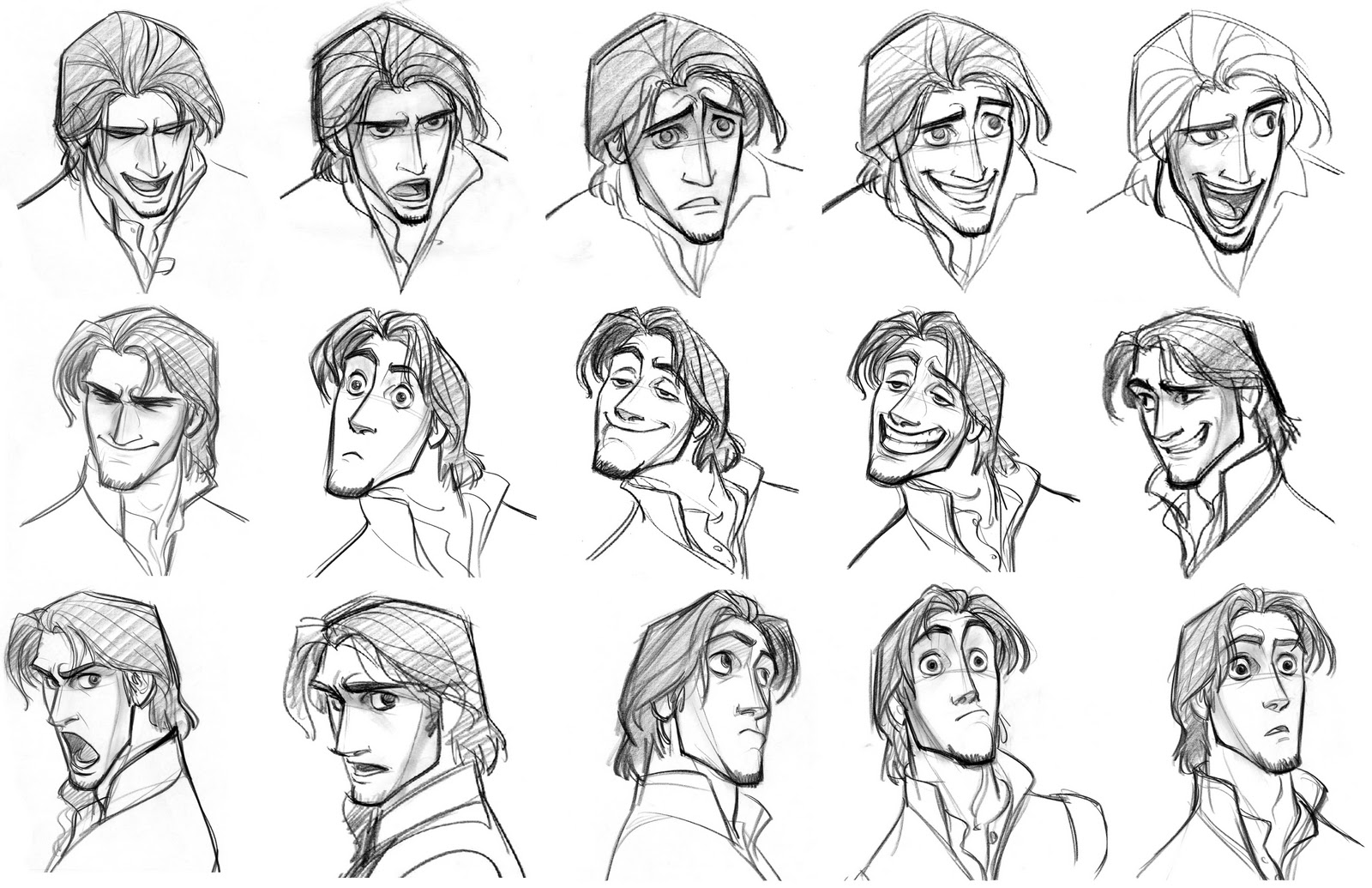

As writers, we often romanticize our protagonists, endowing them with ruggedly handsome, or sweepingly enchanting good looks, special abilities that set them above the fray and add intrigue, and razor dialogue that always leads them to exactly the right thing to say at the right time. Our heroes are, after all, in some way not too short of narcissism, based on ourselves. And don’t we love to pretend we are that cool?

One thing that we definitely do with our protagonist, is give him a sense of duty born from a true conviction. He believes in what he does, and what he does is right and just. This aspect of a character is why he acts and plays out the trials and conflicts in the story. Ultimately, it is also why we as readers follow him into whatever danger his belief conjures.

But what of the villain? Why do so many bad guys fall flat and fail to intrigue readers? And why, as writers, do we spend so little time developing our antagonists as fully as even our sidekicks?

What of a villain bent on world domination, or a bad guy who just likes to kill? Isn’t that good enough to tell a good story?

Look at Grendel from Beowulf. In the original text, the Christian poet uses an ancestry leading back to the biblical Cain as a reason for Grendel’s origin and motivation for his pain. All of Cain’s descendants are out of God’s favor, cursed and twisted and chased into the marshes to live out their miserable lives as monsters and demons. So Grendel, hearing the Danes singing of the Genesis of Man, suffers physical pain which drives him to devour them. Is this any different than eating man to sate a hunger? Grendel poses an honest threat, but is he the true villain, or does Grendel’s mother fill the role?

As readers in a modern culture who question the motivations of everyone we connect with, we demand more than a simple villain archetype. Thus, we need to develop one as writers, but how?

One solution is to tear down the division between how we view our antagonist, and how we view our hero.

(Caveat*** As with anything else, this should not be seen as absolute, merely as an observation that may help get you going!)

Rule #1. A Villain does not see himself as evil:

An honest character is motivated by his own sense of right. The morality of your villain must seem to him to be the only right way to improve the world around him.

Example: If the populace is in a state of evolutionary deterioration and the segment of society that is capable of improving the world is failing to reproduce as quickly, a (dastardly) solution might be to use a female segment of the population as surrogate producers for lab created embryos of the elite, and wipe out the remaining members of the populace with a quick acting biological agent (we do, of course, want to be humane!)

In this example, the villain believes himself to be working toward the greater good! He sees his morality as right and just. He may even be able to convince some readers that his plan makes sense. Which leads us to #2.

Rule #2. There is nothing so dangerous as a fanatic:

If the villain truly believes that what she’s doing is right for some general good, twisted as it may seem to us, we (readers) will believe that she is dangerous. If a character simply wants to take over the world, we yawn. Doesn’t everyone want that in some small way? But if a character believes that she needs to rule the world in order to right some wrong, and that she is the only one who can do it properly and by virtue of that belief will go to lengths involving acids, disease, and bloodied machetes, then we will sit up and pay attention.

Rule #3. Give your villain something to lose:

Just like your protagonist, give your villain something to fight for, and something valuable to lose. As an amendment to this rule, the possible loss should be something that the readers sympathize with. If a bad guy loses his favorite sewer rat, good riddance. No big loss for the reader. But if the villain has a child who is (perhaps as a foil) good and affected only by the events surrounding her, then the audience will feel the loss and allow themselves to understand the villain’s motivations. Not agree with them, but understand them.

Rule #4. Give the villain as many of your own characteristics as you endow your hero with:

We all have a light and a dark side and so should our heroes and baddies. No one is pure evil, not even the devil. He had his own reasons for rebelling. For some reason, giving your villains a few of your better traits (honor, honesty, charisma, wit, kindness toward children or animals) can make your audience hate them even more deeply.

We don’t want to identify with villains. It confuses us. We want to believe the best of who we are, and ignore and deny the worst. The most intriguing moment of a story is when a villain begins to convince a reader that what he is doing may actually be necessary, no matter how vicious or unimaginable. This is exactly why we need to identify with the worst of ourselves and the best of ourselves in the very characters we’re supposed to be rooting against.

If you make your villain like you, you’ll connect to him and a part of you will want him to succeed.

Rule #5. Learn to love your bad self:

Let that translate into your villain. Let her believe in her cause and believe that she is really the solution, the protagonist, the hero.

Enjoy the darker side. Play in the deep, dark waters with the monsters of your subconscious. Then, give your protagonist the power to win your audience back and send the forces of evil into the fiery pit of oblivion. You might just enjoy yourself.

Go write.